Ros Wright helps trainers preparing candidates for OET Speaking

I often start OET Speaking sessions with a quote from the 20th century Canadian physician William Osler: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

Never is this quotation more pertinent than when stressing the need for a patient- centred approach in healthcare. At the heart of a patient centred approach – one that considers the patient as a whole rather than a set of symptoms – is empathy; a skill not easy to achieve, but one that is key to success in OET Speaking. The subject of empathy is vast, but I hope to provide some insight for those new to OET as well as a few pointers to help develop this all-important skill with your candidates.

Introducing OET Speaking

The Occupational English Test (OET) assesses language proficiency in 12 different healthcare professions, from doctors and nurses to podiatrists, speech therapists and vets. OET Speaking consists of two short role-plays, e.g. advising on lifestyle changes, during which candidates are assessed on both their linguistic (including grammatical expression, lexis and pronunciation) and their clinical communication skills. Clinical communication skills essentially refer to what many in ELT know as ‘soft skills’ and indicate a patient-centred approach to care. Five clinical communication skills are assessed, amongst those, relationship building with empathy as an essential component.

Demonstrating empathy – how easy is it?

In the field of veterinary surgery, failure to demonstrate empathy is one of the most common causes of official complaints from pet owners (Shaw et al, 2004). Indeed,

studies of healthcare professionals in general have found that opportunities to demonstrate empathy are regularly missed. Even when they are acted upon, practitioners tend to focus on the situation, “How did she die?”, rather than the impact on the patient, e.g. “How is it affecting you?” (Hsu, 2012); the latter indicating a level of empathy.

Not unsurprisingly, allied healthcare professionals are considered the best at expressing empathy, while women (veterinary surgeons included) are generally more adept than their male counterparts. When it comes to skills development, Marsden (2014) found that explicit rather implicit training was preferred by medical students, with focus on the benefits of empathy; an approach worth considering when preparing OET candidates.

Empathy – what it is and what it’s not

For Goleman (2011), empathy is, ‘the capacity to understand the other’s predicament and to feel with them but also to spontaneously want to take action to help them’. While sympathy is an appropriate and acceptable acknowledgement of suffering, it doesn’t go quite far enough.

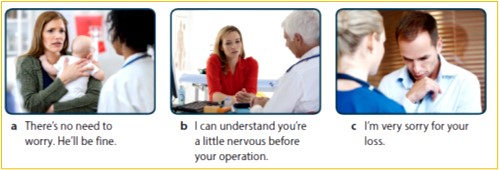

Candidates are usually unaware of the difference between sympathy and empathy and how they are expressed in English. When someone dies, we often hear people say, “I’m sorry for your loss.” or “I was really sorry to hear about your father”. Candidates reproduce these, not realising that, unless substantiated, they tend to denote sympathy rather than empathy.

In a healthcare context, sympathy is a problem. It can create distance and pity, and even go so far as to impair the professional’s ability to care for a patient effectively. A patient who is pitied feels inferior and disempowered. Empathy, on the other hand, tries to see the situation from the patient’s point of view. By empathising, the practitioner is trying to understand their mindset and emotions without being judgemental. Empathy is about building a relationship and connecting with the patient.

“Candidates are usually unaware of the difference between sympathy and empathy and how they are expressed in English.”

A useful starting point when preparing candidates is to gauge their understanding of the differences between sympathy and empathy. Ask candidates to analyse common responses to patient emotion and discuss their level of effectiveness. How empathetic are these responses (below)?

Silverman (2013) suggests demonstrating empathy is a two-stage process: healthcare professionals need first to understand and appreciate their patient’s situation or how they are feeling, and then, most importantly, ‘communicate that understanding back to the patient in a supportive way.’

To do this, candidates should be encouraged to read patient cues (verbal or non-verbal) and name the patient’s emotion, whether it be anger, frustration or distress, e.g. “I can see this is rather distressing for you.” “I can appreciate how angry this must make you feel.” In doing so, not only does the candidate reinforce their expression of empathy; he or she also demonstrates to the examiner an understanding of the situation and its impact from the patient’s perspective.

There are different kinds of empathy, notably direct and indirect empathy. If empathy is about making a connection, what better way than sharing your own experience with the patient? The candidate who has experienced the anxiety of taking their own child to hospital might say, “I can understand your anxiety. I recently had to take my child to A&E with a broken arm. Please let me reassure you that you did the right thing bringing Benjamin in to see us today.” Even if your candidate is not a parent, this is still a technique they could use on test day. In the case of indirect empathy, the above example, “I can appreciate how angry this must make you feel,” shows the patient you are with them, even if you haven’t experienced the exact same situation personally.

Empathy – an ongoing process

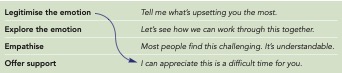

Demonstrating empathy requires more than just a single statement of expression. It is an ongoing process of recognising cues and interpreting meaning, exploring the patient’s emotion, as well as legitimising feelings and concerns and providing support.

Legitimising the patient’s concerns, e.g.

“Most people find this challenging. It’s understandable,” validates and normalises their emotion. Exploring the emotion with an open question, “Tell me what’s upsetting you the most,” helps the candidate better understand the patient’s perspective. And in offering support, the practitioner reinforces the desire to work together as a team. This is further reiterated with use of, ‘we’ e.g. “I can appreciate this is a difficult time. Let’s see how we can work through this together.”

To develop their usage, asking candidates to match phrases to the appropriate headings, generally works well (see table, top right).

This can be followed by an activity whereby candidates notice the language in context, preferably in an authentic dialogue between practitioner and patient.

Empathy and non-verbal communication

Empathy is not simply about employing the right expression at the right time. In her TEDx Talk, The Power of Empathy, Dr Helen Reiss highlights the importance of non-verbal communication in empathy. Eye contact generally indicates the healthcare professional is giving the patient their full attention, and therefore according them the respect they deserve; a first step in demonstrating empathy.

Further to this, positive facial expressions help convey warmth and compassion, while an open posture avoids creating a physical barrier with the patient. She cites doctors on ward rounds who sit rather than stand. They are often considered more caring than their colleagues, even if they use exactly the same words.

Finally, Dr Reiss encourages healthcare professionals to ‘hear the whole person,’ not simply the words they use. Is there a crack in the voice denoting sadness or a look away to suggest embarrassment? Both require further exploration and, of course, empathy.

Although in OET Speaking, role-plays are audio recorded, the development of non- verbal skills should not be ignored. Similar to the customer service employee trained to smile on the phone, OET candidates will find their non-verbal communication skills help reinforce the empathetic process.

Empathy – delivering the right message

Ensuring any well-chosen expressions convey the message intended, focus must be given to the development of appropriate intonation and tone of voice. In this instance, candidates will do well to notice native speaker usage. YouTube provides a plethora of examples, while listening test samples on the OET website could also be utilised for the same purpose.

Encourage candidates to record their voice and replicate the patterns they hear. Finally, pausing is a simple but invaluable technique that helps denote empathy, affording patients ‘space’ to collect their thoughts and assimilate potentially difficult information.

Conclusion

The question of whether valuable time is wasted in engaging in empathy has long been cause for debate. Indeed, this may well be the concern of some candidates, especially given the time constraints of the OET role play (approximately 5 minutes). In response, however, Anfossi and Numico (2004) point out that expressing empathy should not take time out from clinical work, rather it should be, ‘embodied in the physician’s overall attitude …’ I recently came across the embodiment of empathy in the form of Mark, a consultant appearing in 24 hours in A&E, (Channel 4), seen here (below left), communicating with 95-year-old Sylvia.

See Wayne Trotman’s full review here.

REFERENCES

Anfossi, M. and G. Numico (2004) ‘Empathy in the doctor-patient relationship’, Journal of Clinical Oncology

Golman, D., (2011) The Power of Emotional Intelligence

Marsden, AJ., (2014) Empathetic Consultation Skills in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Qualitative Approach PhD thesis, University of East Anglia Norwich Medical School

Shaw JR, Adams CL, Bonnett BN. What can veterinarians learn from studies of physician- patient communication about veterinarian-client-patient communication? JAVMA 2004; 224(5): 676-684

Silverman, J., (2013) Skills for Communicating with Patients, 3rd ed., Taylor & Francis

Wright, R., (2020). OET Speaking & Writing Skills Builder, Express Publishing

The official Occupational English Test site provides detailed information about OET Speaking, including sample tests and the marking criteria. https://www.occupationalenglishtest. org/test-information/speaking/