Demography is the real danger, says Melanie Butler

The mood in European EFL is generally glum. And it’s not just Brexit. I’ve been getting e-mails from Spain predicting the death of the language school, and tweets from British teachers from Posnan to Padova, complaining they cannot live on their salaries. Pity the poor foreign lettori in Italy who, as we report on page 4, have been fighting for their rights for thirty years, and now the British lettori may risk losing everything.

Even the universities are moaning. On page 7 we reveal the Dutch have so many international degree students they have to house them in shipping containers, while on page 4 we find French universities have put their fees up in an effort to attract more students.

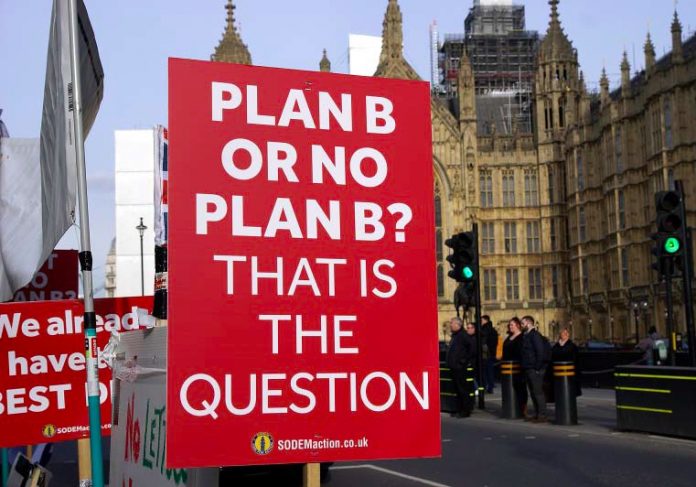

Now for the good news. With UK Brexit plans in chaos, the European parliament has rushed to protect European students on Erasmus courses in the UK, as we report on page 5 of this supplement.

Meanwhile, on the same page, we report how the Irish are rubbing their hands at the prospect of cornering the EU market. On page 9, we note that Malta is rolling out the work visas as their long-haul student market grows.

Best news of all, at least for their governments, the language levels of students in Italy and Spain are rising. The main reason seems to be the rise and rise of CLIL and bilingual programmes in the state sector. This may be bad news for local language schools in Milan and Madrid, because parents don’t feel the need to top up their child’s English with a twice-weekly language lesson. But it doesn’t seem to be having much impact on the market for summer schools.

But the choice of summer courses is changing.

Some are looking for hard-CLIL courses with specialist teachers – easy enough for boarding schools, though the cost of such teachers is putting an extra strain on private sector providers, as we explain on page 11.

Others are demanding proper sports courses with professional coaches (see page 12).

“The irony is, of course… that Europe is running out of children.”

Agents also report a switch from summer courses to year-round provision. The demand for academic, year-round immersion courses in state secondary schools is growing, especially in Ireland where, as we report on page 13, language schools have led the campaign to regulate the guardianship sector.

Brexit or no Brexit, the move, it is clear, is for EFL to become part of education, rather than just a variation on the junior activity holiday with a bit of English grammar thrown in.

The under-16 market is also growing outside the traditional summer season and the UK has responded to the surge in groups of young learners coming for short courses in the low season by increasing the number of schools which specialise in the sector. Teaching young learners is a whole different ball game from the adult market, as Kevin McNally of Torquay International School explains on page 16.

Torquay is just one of the towns in Devon which makes that region the young learners centre of the UK. As we explain on page 15, schools have been enrolling under-16s here for many years, and the policies of the local authorities help make it one of the safest places to send children.

The irony, of course, in the growth of the young-learners’ language travel market, is that Europe is running out of children. Half the population in the EU is over the age of 46, only 15 per cent is under 15.

This demographic squeeze is about to hit not only the supply of young learners but the supply of teachers. For every 18-year-old in the UK there are two people aged 50. The situation in Ireland, which has the youngest population in the EU. may be better, but don’t expect a flood of Irish graduates to fill the post-Brexit shortfall. The graduate unemployment rate in the Republic is just 5 per cent.

Maybe it is not Brexit that poses the biggest threat to the EFL market across the EU, but demographics.